Natural Gas Dehydration: Lessons Learned from the Natural Gas STAR Program

September 13, 2007TEDX to NYC Council: "The western experience should be taken seriously by those in the East"

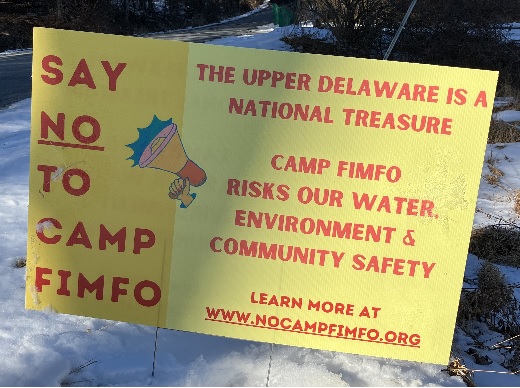

September 9, 2008We believe that letting natural gas companies pockmark our area with natural gas drill holes is a bad idea. The costs of doing so include depletion and contamination of our aquifers; noise, light and view-shed pollution; subsidence of properties under which gas is mined; fragmentation of habitat; and the potential decline of property values.

But the benefits to the landowners in question can be huge, and this particular issue, which gets right to the heart to the perennial conflict between private property rights and the greater good, is not altogether black and white.

Regardless of how we or anyone else feels about having gas wells as neighbors, the people being asked to sign leases to allow such drilling do own the land in question. To say that they should be forbidden to sign such leases “for the greater good” is uncomfortably reminiscent of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which empowers companies like New York Regional Interconnect (NYRI) to seize private land to construct power lines in the name of the “national interest.”

Moreover, many of the large tracts of land that would naturally be targeted by gas companies are presumably owned by farmers. We have spent a lot of time recently belly-aching about the plight of the farmer; it seems scarcely consistent to tell them, now that they’ve found a source of funds, that they shouldn’t be allowed to take advantage of it.

Nor are farmers the only group suffering hardship locally, especially in a deteriorating economy. Some landowners may be facing huge medical bills, due either to lack of coverage or to medical insurance companies’ refusal of their claims; and still others may face foreclosure in the mounting real estate crisis. The type of money that is being talked about, ranging from about $75 per acre to almost $500, would be a godsend to such people.

The problem is that individual property rights and the greater good are both important. Neither should be demonized and neither should be made absolute. And balancing them is not something that can be done in the abstract; it has to be worked out on a case-by-case basis.

It’s too early to see exactly where that line falls in the current instance, but there is one principle that we would like to bring to the forefront of the decision-making process: schemes to get rich quick all too often turn out to be a great way to get poor slow.

We are a low-income rural community whose “riches” primarily take the form of as-yet undespoiled natural resources. Financial desperation all too frequently drives us to seek ways to make money by the shortest and easiest route: liquidating those resources. Our beautiful open land makes us a tourist destination, so we plan to build big, high-tech, high-traffic casinos on the land—a plan that would destroy the asset that makes us attractive in the first place. Our land may have minerals under it, so we plan to drill and mine it. Not only could that destroy the value of the land for tourist, outdoor sport, watershed and just plain quality-of-life purposes, but in a couple of generations the minerals would be gone, leaving only ruin behind them.

But there is another way. Instead of liquidating our assets, we can nurture them so that they will yield returns into the indefinite future. Bethel Woods Center for the Arts is such a use. The establishment of green cemeteries, as discussed in our editorial of October 25, 2007, might be another. Agri-tourism would be a third. Wind farms are more controversial; some believe they destroy the view-shed, others find them attractive in their own right.

But if we must sacrifice our land to energy production, let it at least be to a sustainable source, not to a dinosaur like natural gas that exacerbates global warming and is part of an obsolescent technology.

As a community, we need to get out in front of the problem of how to take care of our members financially without plundering our shared treasure. The more aggressively we can promote livelihoods that involve nurturing rather than liquidating our natural resources, the more choices we can present to landowners who feel they must sacrifice their land in order to survive—and the greater chance we have to leave our progeny something more than an empty coffer.