By JOEL KIRKLAND of ClimateWire, July 9, 2010

PITTSBURGH — Around suppertime on June 3 in Clearfield County, Pa., a geyser of natural gas and sludge began shooting out of a well called Punxsutawney Hunting Club 36. The toxic stew of gas, salt water, mud and chemicals went 75 feet into the air for 16 hours. Some of this mess seeped into a stream northeast of Pittsburgh.

Four days later, as authorities were cleaning up the debris in Pennsylvania, an explosion burned seven workers at a gas well on the site of an abandoned coal mine outside of Moundsville, W.Va., just southwest of Pittsburgh.

The back-to-back emergencies were like a five-alarm fire for John Hanger, secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. For a brief moment, the cable news channels turned their attention away from the BP PLC oil gusher in the Gulf of Mexico to the apparent trouble in the nation’s expanding onshore natural gas fields.

The events added force to a tough public debate in Pennsylvania and New York and across northern Appalachia about how the environmental impacts of gas drilling balance against the economic benefits of gas and the role it could play in helping electric utilities transition to cleaner fuels.

When used to fire up a power plant, natural gas produces less air pollutants and half of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by conventional coal plants. But extracting the gas from deep sedimentary rock and shipping it to consumers is an industrial process. It requires massive amounts of water and reliable cement and pipe jobs. It also has wastewater-disposal issues and generates air pollution.

“This is a test for people in public life,” Hanger says. “Do you get into public service to treat the gas industry fairly and protect our resources, or not? You don’t have to choose between producing the gas and protecting our water.”

The extent to which U.S. utilities will burn natural gas to slash carbon dioxide emissions tied to global warming is a national issue. But on the ground, where it’s being produced, all politics is very local.

Regulators ‘over their heads and drowning’?

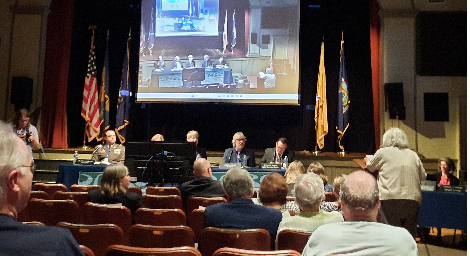

Hanger is a contentious figure in Pennsylvania. He personifies the state’s willingness, or lack thereof, to police drillers operating in the Marcellus Shale natural gas basin under Pennsylvania. At public forums where residents bring their environmental concerns, Hanger’s name and the administration of Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell (D) attract a mixed bag of praise and frustration.

“They need to admit that they’re over their heads and drowning,” says Jon Bogle, founder of the Responsible Drilling Alliance, a citizens group in northeastern Pennsylvania, the epicenter of Marcellus drilling activity so far this year. “They are trying. They’ve toughened their position. They just don’t have the personnel to do the job.”

To some residents, Hanger has shown in recent months he’s serious about getting compliance from drillers by fining companies and forcing them to plug poorly constructed wells.

To others, development is rapidly outpacing environmental safeguards. The geyser in Clearfield County, the fire in West Virginia and high-profile cases of groundwater contamination in Dimock, Pa., underscore their belief that regulators in the Northeast have been outmanned and outmaneuvered by a powerful industry imported from the friendlier confines of Fort Worth, Texas.

“We’re not running a see-no-evil, hear-no-evil regulatory apparatus here,” Hanger responds. “We’re working on rules and regulations that should have been addressed a decade ago.”

A hangover from the impacts of coal mining

Pennsylvania’s struggle with gas production is tied as closely to coal as it is to anything else. Coal mining is built into the social topography of Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley. Centuries of mining, from southern Illinois to the Allegheny Mountains, fortified the rural economies but fostered acrimony and distrust among landowners, conservationists and coal companies. Pennsylvania struggles to control acid mine runoff from abandoned coal mines.

“One of the greatest challenges is convincing people that we are not the second coming of coal,” says Matt Pitzarella, spokesman for gas producer Range Resources.

Coal informs discussions about the gas rigs and leases cut into the forests and farmland. And the recent flurry of environmental disasters in oil and coal fields has fueled fears about the impact the gas boom will have on aquifers, fragile ecosystems and public health.

BP’s Gulf disaster stiffened the resolve of environmental groups in Pennsylvania and New York to challenge industry guarantees about the safety of modern hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) technology used to crack deep deposits of gas-rich shale rock.

The collapsed coal-ash containment pond at the Tennessee Valley Authority power plant in Kingston, Tenn., raised questions about leaks at similar waste pits located on gas drilling sites. And the explosion in April that killed 29 people at the Upper Big Branch coal mine in West Virginia offered a bleak reminder of the dangers of this kind of work.

Gas producers maintain that the use of horizontal drills to extract gas from under neighboring plots means drillers require less land for well pads and equipment. They argue that chemicals pumped into the ground are benign, aquifers are protected by steel and concrete, drilling requires less water than nuclear power or a coal-fired power plant, and companies can dispose of salt water without poisoning streams.

The hotbed of environmental protest about the potential impact of drilling is in New York, where the source of New York City’s drinking water is the Catskill Mountains and Delaware River watershed on the eastern edge of the Marcellus Shale. The water supply is fed by underground aquifers and the area’s rivers and streams, and the water is pristine enough to flow unfiltered through a system of aqueducts to 9 million New York residents.

Public distrust spreads from N.Y.

There, public distrust of gas companies has engendered less tolerance for political equanimity. Polluting the aquifer and using too much of the water are the central concerns. A de facto moratorium on drilling the shale already exists, but lawmakers in Albany are considering codifying a one-year moratorium until regulators finish environmental impact studies.

As public protests mounted last fall, Chesapeake Energy CEO Aubrey McClendon extended an olive branch and promised not to drill his leases in the watershed. In January, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg urged Gov. David Paterson (D) to put the water supply ahead of the economic benefits to a state $7 billion in the red.

“July 14 may be the most important date this summer in the Delaware River Watershed!” shouts a recent e-mail blast from the Delaware Riverkeeper Network. “Moratorium is needed on all gas projects!”

The group, which targets water pollution in the basin at the confluence of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, regularly petitions the Delaware River Basin Commission. July 14 is the date of the commission’s upcoming meeting. The region’s governors are members of the commission, and it sits far enough from politics and the day-to-day lobbying in Harrisburg and Albany to act boldly on petitions to stop drilling in protected areas of the water basin.

In the past few months, the commission has done just that. One pending project, a Stone Energy Corp. plan to develop a gas well in Wayne County, Pa., garnered 2,000 written comments, many of which urged the panel to call a development time-out. To that end, the commission has issued sweeping directives since May forcing gas project sponsors, including Stone, to be permitted before drilling production or exploratory wells. And the panel has said it plans to set aside most applications until it adopts regulations for gas drilling in the Marcellus.

Regulate first, drill later

“Your pro-gas drilling forces might see us as impeding the process, and state regulations are sufficient,” said commission spokeswoman Katharine O’Hara. “But we are the states,” she added. “We’re not trying to stymie the industry or overstep. Our goal is to ensure this is done in a responsible way and that it doesn’t harm or degrade the resources in the basin.”

Pennsylvania politics doesn’t separate pro-growth politicians from their environmental opponents with neat lines of demarcation. The state continues the search to find middle ground.

But increasingly, in some corners, the measured debate in Penn’s Woods has been drowned out by hyperbole and accusations that the other side is being disingenuous. And the New York glare from “Gasland,” an HBO documentary by filmmaker Josh Fox, has stirred passions on both sides.

In it, Fox raises the specter of unchecked corporate power as gas rigs proliferate across the Pennsylvania landscape, poisoning the groundwater and ruining people’s lives. The gas industry has condemned the film as environmental propaganda and wildly exaggerated.

The tone of the film aside, the Marcellus debate in Pennsylvania still rests in the middle and is almost entirely about the still-evolving science of hydrology.

“We’re all affected by what happens in the watersheds,” said Jeanne VanBriesen, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University and director of the Center for Water Quality in Urban Environmental Systems. “Water here moves in and out of urban and rural environments.”

Salty water and fish kills

Climate change and recent gas drilling-related events have illuminated the difficulties scientists face in pinpointing sources of pollution and the way water flows through the complex watershed.

“Water predictions are based on historical records on what’s happened in a watershed,” she explained. “Global climate change is really a game changer for hydro-modeling. The climate is changing in a way that is unsuitable for future predictions.”

Like coal, the rapid industrial development of natural gas adds to concerns about water usage and disposal. “To understand what it means to use the water for Marcellus development,” VanBriesen said, “we need to understand where it goes. If you think we know where all the water is going, you’re wrong.”

In September 2009, a toxic algae bloom killed a massive amount of fish and aquatic life along a 43-mile stretch of Dunkard Creek on the Pennsylvania-West Virginia border. By year’s end, a U.S. EPA report had fingered the legal practice of dumping wastewater from a Consol Energy coal mine into the creek as one of the most likely causes, but not the only cause.

Discharges into the creek, according to EPA, included a high level of total dissolved solids (TDS) that probably created the salty conditions needed for the poisonous algae to bloom. TDS measures amounts of sodium, chlorides, sulfates, nitrates, carbonates and other minerals, and while they aren’t considered major pollutants, they can foul fresh water. Water quality specialists consider TDS levels to be an indicator that other chemical contaminants are in the water.

After the fish kill, environmental activists said the high TDS levels could just as likely come from gas drilling in the area, which also extracts huge amounts of salt-laden, high-TDS water from the ground. As much as half of the millions of gallons of water injected into the earth when companies drill or fracture the shale returns to the surface contaminated and extremely salty. Coal and gas companies are supposed to strip out the metals before disposing of the water. The region’s geology makes it difficult to re-inject water, and recycling is not yet widespread, in part because of the cost of the process.

Investigators are still looking at what caused the fish slaughter at Dunkard Creek, but VanBriesen said there’s strong support for the conclusion that algae thrive in salty conditions.

“The impact of total dissolved solids more broadly on watersheds and ecosystems is less well understood,” she said. Still, she asserted, “allowing rivers and creeks to get very salty is not good for the ecosystem.”

Dimock, a northeastern Pennsylvania township where residents accused Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. of poisoning their water wells, has become a well-known symbol of the troubles in gas country.

Busted gas wells and the migration of methane into water wells put the challenge to Hanger. In April, the DEP ordered Cabot to plug three wells believed to be the source of migrating gas. The agency ordered Cabot to suspend the drilling of new wells for a year in and around Dimock, and it fined Cabot $240,000.

‘What legacy will we leave?’

Gas industry groups have defended Cabot. They argue that shallow methane is a naturally occurring phenomenon in Pennsylvania, a pre-existing condition that shouldn’t be laid at the feet of a new industry.

In Pennsylvania, unlike in New York, there are legal limits to actions a regulator can take to stop a company from operating. Hanger has asked the Legislature for clear authority to withhold new permits for companies that repeatedly violate rules.

Hanger’s DEP has hired more inspectors this year. With the support of environmental groups and some gas companies, the DEP also pushed for water quality regulatory reforms that a few weeks ago received the go-ahead from an independent review board in Pennsylvania. The new rules require gas producers to treat wastewater to the same quality as drinking water before dumping it into a stream. That means ensuring TDS levels don’t exceed 500 milligrams per liter. The new rules also establish buffer zones for drilling around critical waterways.

On Tuesday, Gov. Rendell signed a $28 billion state budget that, as part of an agreement among legislative leaders, includes a pledge to develop a severance tax on gas production by Oct. 1. It has been among the stickiest issues for lawmakers. Few in Harrisburg said they wanted to slow the economic growth, but in recent months, broad support grew for crafting a tax to help pay for environmental cleanup and local costs incurred because of the drilling.

Rendell, who tends to emphasize both the economic opportunity and the environmental hazards, gave Hanger and another member of the governor’s inner circle, John Quigley, secretary of the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, the green light this year to sharpen their tone against the gas industry.

The three have kept the pressure on with regard to the tax on gas. “It is difficult for me to swallow the argument that an industry led by the likes of Exxon, one of the largest companies in the world, is in fact an infant industry,” Quigley said at a conference in Pittsburgh in May. “To suggest we should wait to tax the industry strains credulity.”

The Marcellus Shale Coalition, which represents the major Marcellus gas producers, has opposed the tax, arguing that saddling producers with a tax on production of anywhere from 4 to 8 percent could stifle development in the early stages.

The group’s president, Kathryn Klaber, has crisscrossed the state to press the industry’s case. “If you tax something, you get less,” she says. “Not everyone takes this economic argument to heart.”

More than 7 million Pennsylvania acres is now under lease for gas exploration, about one-quarter of the state’s landmass. At a conference in Pittsburgh in May, Quigley called on citizens groups to protest proposals to expand leasing in state parks. “There are those who would ignore the questions of balance and sustainability, who would look to the public lands to balance the budget without regard to consequence,” he told the packed room at Duquesne University. “What legacy will we leave? Will we continue to burn the furniture to heat the house?”