Insight: Peak, Pause or Plummet? Shale Oil Costs at Crossroads

May 23, 2012Report Reveals Few Penalties for Violating Gas Drilling Rules in PA

May 23, 2012By Ronald Steinvurzel and Jessica Buno, New York Law Journal, May 23, 2012

The war over natural gas extraction from Marcellus Shale deposits is being fought from the ground up. The extraction methodology now preferred for its efficiencies is hydraulic fracturing. “Hydro-fracking” is a method that increases well productivity by fracturing the geologic formation in which resides the objective resource thereby increasing the drainage area of the well.1 This process was first patented in 1953 and has been utilized in various well drilling applications such as well bore repair, assisting with secondary recovery and disposal of wastes.2

In recent years hydro-fracking has become quite popular in natural gas recovery particularly in the Marcellus Shale deposits. In this application, the technique consists of drilling a natural gas recovery well several thousand feet below ground surface and then turning the well horizontally through the Marcellus Shale.3 High pressure fluids are injected deep into the well to fracture the dense shale formations in which the natural gas is trapped. This “frack fluid” contains proppants such as sand, ceramics or other particulates that are pumped into the fractures to keep the fractures dilated while the gas is extracted.4

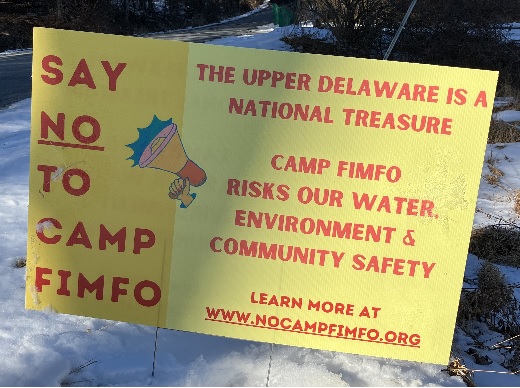

Oil and gas companies have long realized profits paying private landowners to lease subterranean oil, gas and mineral extraction rights. However, the construction and drilling of just one well for hydro-fracking requires millions of gallons of water (including frack fluid), all of which is transported across local roads in large, heavy trucks. Local governments are left to deal with deteriorated roads, damaged vegetation and increased noise and traffic pollution. Residents have also expressed concern about the dangers associated with transportation over local roadways of the potentially hazardous frack fluid and the potential for groundwater contamination. Well and groundwater treatment works operators argue that when done properly, hydro-fracking can be made safe. Despite the benefits to local economies coming from new jobs and tax revenues, many municipalities are nonetheless averse to hydro-fracking.

Two recent decisions handed down by the New York State Supreme Court concern the struggle between private landowners seeking to lease their lands for gas extraction and local municipalities seeking to ban oil and gas drilling through land use regulation. This would not be the first time local governments sought to control or restrict industrial operations via land use regulation, but it does appear to be the first of such restrictions directed toward hydro-fracking.

On Feb. 24, 2012, in Cooperstown Holstein v. Town of Middlefield (Otsego County),5 acting Supreme Court Justice Donald Cerio stated that local municipalities have constitutional and statutory authority to allow or prohibit oil, gas and solution mining or drilling. On June 14, 2011, the Town of Middlefield enacted a local zoning law effectively banning oil and gas drilling. Article V of the Middlefield Zoning Law titled “General Regulations Applying to All Districts,” prohibits any and all oil, gas or solution mining and drilling within the municipality.6

Jennifer Huntington, a dairy farmer and president of Cooperstown Holstein Corporation, had previously signed two oil and gas leases authorizing Elexco Land Services Inc. to drill and extract natural gas captured in the Marcellus Shale that lay beneath her land.7 Following the enactment of the Middlefield zoning regulation, Cooperstown Holstein brought an action against the municipality arguing that the zoning law is preempted by the New York State Oil, Gas and Solution Mining Law (OGSML).

Cooperstown Holstein relied on the supersession language contained in the OGSML, which states: “[t]he provisions of this article shall supersede all local laws or ordinances relating to the regulation of the oil, gas and solution mining industries; but shall not supersede local government jurisdiction over local roads or the rights of local governments under the real property tax law.”8 The court examined the legislative history and the plain meaning of the statute and concluded that the State of New York did not intend for the preemption to apply solely to “local roads or the rights of local governments under real property law.” Rather municipalities are not prohibited from enacting legislation that completely bans the oil, gas and solution drilling or mining industries.9

The court found it instructive that the legislative history, since the OGSML was enacted in 1963, was silent with regard to the impact or preemption by the state of local municipal land use regulation. Further, the court found it evident from the 1978 amendments that the promotion of energy extraction was a separate and distinct activity from the regulation of energy extraction. The original 1963 language stated, “[i]t is hereby declared to be in the public interest to foster, encourage and promote the development, production and utilization of natural resources of oil and gas in this state….”10 The 1978 amendments replaced the phrase “foster, encourage and promote” with the word “regulate,” thereby charging the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation with the task of moderating the method and manner of drilling. In addition, the same legislation also amended the New York State Energy Law, granting the (former) Energy Office the authority to promote and develop indigenous State energy resources.11 These amendments statutorily and departmentally divided the two tasks as separate and distinct activities. The Department of Environmental Conservation had to deal with properly “regulating” the rapidly growing drilling industry in New York State.

Subsequently, the supersession clause at issue was added in the 1981 amendments to provide uniform standards, expeditious handling of permits and proper state-wide oversight. There was no language to conclude that the supersession clause was enacted to diminish or eliminate a local municipality’s right to enact legislation pertaining to land use.12

The Cooperstown Holstein court found neither the plain reading of the statutory language nor anything in the legislative history to conclude that the language in the OGSML was intended to divest local municipalities of the right to enact laws affecting land use beyond those pertaining to local roads and the municipalities’ rights under the real property law. While the state maintains control over regulating the “how” of exploration, municipalities maintain control over the “where.”13 The Town of Middlefield was not seeking to regulate the method or manner of the mining industry (which would have been preempted by the OGSML), but rather was seeking to control activities that occur within their borders.

The Cooperstown Holstein decision came on the heels of a similar decision from the New York State Supreme Court, Tompkins County. On Feb. 21, 2012, in Anschutz Exploration v. Town of Dryden,14 Supreme Court Justice Phillip R. Rumsey issued a decision of first impression in New York State regarding local governmental powers in the controversy over drilling for natural gas in the Marcellus Shale. The court held that New York State law does not preempt a municipality from utilizing its police powers, even if such exercise may effectuate a de facto ban on oil and gas exploration.

Adversaries of hydro-fracking point to the risk of contaminating ground and surface water supplies. More than 10 percent of the residents of Dryden signed a petition requesting the Town Board ban hydro-fracking. The Town of Dryden subsequently amended its Zoning Ordinance to list exploration for or extraction of natural gas and/or petroleum as a prohibited use.15 Anschutz Exploration previously owned gas leases covering approximately one-third of the Town of Dryden and invested over $5 million within the town. Anschutz brought an action against the town, arguing that the zoning amendment is preempted by the OGSML. The court found that allowing municipalities to regulate hydro-fracking by restricting access to well sites by the trucks carrying water and frack fluid and by imposing additional costs to repair damaged roads is a permissible exercise of the Town’s police powers.

Court of Appeals Opinions

While this is a novel topic for the New York courts as it pertains to oil and gas drilling, the question of a municipality’s right to ban natural resource exploration is not. Both the Cooperstown Holstein and Anschutz Exploration cases relied on two opinions from the Court of Appeals that dealt with this issue in the context of the New York State Mined Land Reclamation Law (MLRL). The supersession clause of the MLRL states, in pertinent part, that “[f]or the purposes stated herein, this title shall supersede all other state and local laws relating to the extractive mining industry.”16

Matter of Frew Run Gravel Prods. v. Town of Carroll,17 concerns an ordinance enacted by the Town of Carroll banning sand and gravel operations in designated districts. The Court of Appeals held that the town zoning regulation does not regulate the mining industry per se but rather regulates land use generally; and the language of the MLRL’s supersession clause was not meant to preempt the local zoning ordinances.18 Almost a decade later, the Court of Appeals affirmed this decision in Matter of Gernatt Asphalt Products v. Town of Sardinia.19 In Gernatt, the court held that a town may completely zone out any extractive industry, despite the presence of a coveted resource, if the land use ordinance is a reasonable exercise of its police powers. The court found that because the change in the zoning was required for the well-being of the community, the Town Board had rationally exercised its police power.20

Both the Cooperstown Holstein and Anschutz Extraction courts found the primary language of the supersession clause in the OGSML to be identical to that found in the MLRL. Thus, because both statutes only preempt regulations “relating to” the applicable industry, the conclusion must be the same, i.e., that the supersession clauses do not preempt local regulation of land use. The supersession clause in the OGSML was only meant to preempt those laws that regulate the operations of oil and gas drilling. Absent a clear expression of legislative intent to preempt local control over land use and zoning, it appears that the war on hydro-fracking will be decided one municipality at a time.

Conclusion

A rather clear distinction has thus been drawn by the two venues, i.e., that a municipality may enact a back door ban of mining and extraction operations by way of regulating the “districts” where mining and extraction will occur and the roadways used to access such areas. Indeed, given the fears arising from the potential environmental impact of the release of frack fluid on the roadways or in the subsurface, it is possible that more municipalities will join the ranks of Cooperstown Holstein and Anschutz Exploration. But, with oil and gas prices on the rise and ongoing fears associated with the U.S. dependence of foreign petroleum, only one thing is clear: The fight is long from over.