Methane Leaks Erode Green Credentials of Natural Gas

January 8, 2013From Industry Insider to Implacable Fracking Opponent

January 8, 2013By Bruce Finley, The Denver Post, Dec. 9, 2012

Oil and gas have contaminated groundwater in 17 percent of the 2,078 spills and slow releases that companies reported to state regulators over the past five years, state data show.

The damage is worse in Weld County, where 40 percent of spills reach groundwater, the data show.

Most of the spills are happening less than 30 feet underground — not in the deep well bores that carry drilling fluids into rock.

State regulators say oil and gas crews typically are working on storage tanks or pipelines when they discover that petroleum material, which can contain cancer-causing benzene, has seeped into soil and reached groundwater. Companies respond with vacuum trucks or by excavating tainted soil.

Contamination of groundwater — along with air emissions, truck traffic and changed landscapes — has spurred public concerns about drilling along Colorado’s Front Range. There are 49,236 active wells statewide, up 31 percent since 2008, with 17,844 in Weld County.

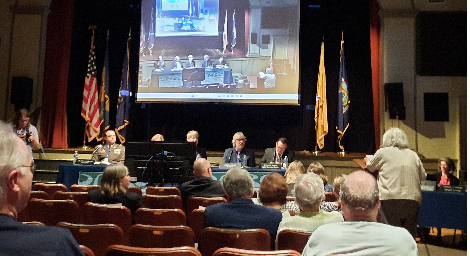

Starting Monday, Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission regulators struggling to maintain a consistent set of state rules governing the industry will begin grappling with the groundwater issue.

The COGCC is weighing proposed changes to state rules that would require companies to conduct before-and-after testing of groundwater around wells to provide baseline data that could be used to hold companies accountable for pollution.

“There is an impact,” COGCC environmental manager Jim Milne said, reviewing the groundwater data. “We don’t know if it is unreasonable or not.”

While spills reaching groundwater are concentrated at the surface, the baseline testing proposals that state commissioners are weighing focus on harm from well bores to deep aquifers.

The proposals do not specify the depths from which samples would be taken. Any existing wells — shallow agricultural wells or deep domestic wells — could be used to draw before-and-after water samples from areas around oil and gas production wells.

One proposal developed by Shell and the Environmental Defense Fund would require testing of three samples of water within 12 months before drilling using wells within a half-mile of a vertical oil or gas well.

Companies would then repeat the tests six to 12 months after drilling is done, and again 60 to 72 months after drilling. At least two of the samples would be taken downslope from the production well.

“It is a very rigorous standard,” EDF regional director Dan Grossman said. “If you put in a robust system, you can bolster confidence of people in the state that these actions are being done responsibly.”

The state government’s efforts to toughen rules around groundwater — such as establishing bigger setbacks around occupied buildings, including churches and schools — are aimed partly at defusing regulatory conflicts between the state and local governments. The COGCC is charged with both promoting and regulating the oil- and-gas industry.

But Boulder County and other local governments have begun to pass health and safety regulations of their own. Longmont adopted tougher city rules that prompted Gov. John Hickenlooper to file a lawsuit challenging local authority. Hickenlooper has warned that a mishmash of varied local rules could drive companies to other states.

Longmont residents then voted to ban all drilling inside the city — igniting ban campaigns elsewhere. Hickenlooper on Thursday said the state will not sue over the ban but will support private companies that choose to do so.

Current proposals for baseline testing of groundwater give companies too much freedom to cherry-pick wells they would use to draw samples, said Gary Wockner, director of Clean Water Action, which is pushing for new local rules in several locations.

“The groundwater sampling would need to be scientifically designed to confirm whether there’s been damage to groundwater — whether deep in the aquifers or at the surface,” Wockner said. “The state needs to clamp down … and protect the public from cancer-causing fracking chemicals.”

Western Resources Advocates attorney Mike Chiropolos pointed out that horizontal drilling — a mile or more away from central vertical production wells — creates new possibilities for groundwater contamination for which baseline data should be available to help measure harm.

Oil-and-gas-industry companies are raising concerns that new rules could impose undue burdens. Companies over a decade probably would have to pay tens of millions of dollars, with contractor costs for groundwater tests ranging from $1,500 to $2,500 per sample, Colorado Oil and Gas Association attorney Ken Wonstolen said.

Most companies already voluntarily do some baseline testing of groundwater.

COGA officials last week said they supported mandatory testing but added they are working at recommending an alternative proposal for a sensible approach. They argued, in pre-hearing filings, that “surface spills and releases are readily discoverable” compared with the potential for well-casing failures deep underground and that any new rule “should be restricted to drilling and completion operations.”

The oil-and-gas industry “is stepping up, saying we understand there is a public concern here,” Wonstolen said. “This program will build public confidence, and we think it’s a good thing to do.”