Living in the Shadow of Danger

January 29, 2016CO & CA: Getting Gassed Together

February 1, 2016By Sarah Smith, SNL Financial, September 9, 2015

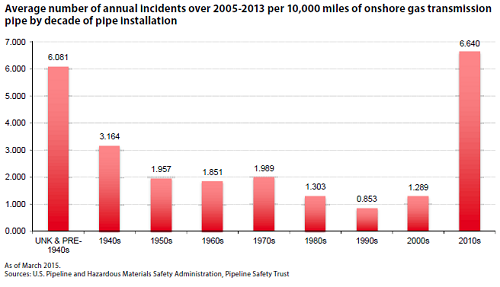

The push to build new pipelines to transport abundant shale supplies appears to be having a materially adverse impact on pipeline safety.

According to a Pipeline Safety Trust analysis of federal data, new pipelines are failing at a rate on par with gas transmission lines installed before the 1940s.

“I think new models of anything — a new model of a car, a new computer, whatever — have problems when they’re first put in. You have to get the kinks out. That’s probably part of the explanation, but there’s also some suggestions that we’re trying to put so many new miles of pipeline in the ground so fast that people aren’t doing construction … the way they ought to,” Carl Weimer, director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, told attendees at a National Association of Pipeline Safety Representatives annual meeting in Tempe, Ariz.

“The new pipelines are failing even worse than the oldest pipelines,” he said.

The trust looked at the annual average number of incidents per 10,000 miles of onshore transmission lines over 2005-2013 based on when the pipelines were installed, as reported to the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

The safety watchdog found a so-called bathtub curve with high points on the ends and low points in the middle, indicating that the oldest pipes and the newest pipes had the highest rates of incidents.

The gas transmission lines installed in the 2010s had an annual average incident rate of 6.64 per 10,000 miles over the time frame considered, even exceeding that of the pre-1940s pipes. Those installed prior to 1940 or at unknown dates had an incident rate of 6.08 per 10,000 miles.

The next highest incident rate was for pipes installed during the 1940s, which had an annual average of 3.164 per 10,000 miles. All other pipe installation decades had annual average incidents during 2005-2013 ranging between 0.85 and 2 per 10,000 miles.

Robert Miller, chairman of the National Association of Pipeline Safety Representatives, or NAPSR, said in a Sept. 1 interview that safety inspections for a while were heavily focused on existing infrastructure, especially as the threats of aging cast iron and unprotected steel became evident. But as pipeline construction has picked up in recent years — particularly in light of the booming oil and gas industry and pipeline operators’ accelerated system replacement work — more emphasis has been placed on construction inspections. However, the heightened focus on construction inspections may not be catching everything, Miller noted.

“If it’s brand new, if it’s all new materials, if everybody was doing their job correctly, why would we have an uptick in … failures?” Miller, who is also the Arizona Corporation Commission’s pipeline safety section supervisor, said. “You can only attribute that, in my personal opinion, to poor construction practices or maybe not enough quality control, quality assurance programs out there to catch these problems before those pipelines go into service.”

For instance, the National Transportation Safety Board in June found that poor pipe fusion in 2011 contributed to a March 2014 Harlem gas explosion that leveled two buildings on Park Avenue, killed eight people, injured at least 50 others and resulted in the evacuations of 100 families.

Examining the relevant plastic joint post-accident, NTSB staff found that 60% of the bond had been incompletely fused, indicating a weld defect and weak bond strength, which prevented the high-density polyethylene pipe from withstanding underground shifting. However, at the time, the board did not express concerns that other, similar fusions are pervasive.

Robert Hall, director of the NTSB’s Office of Railroad, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Investigations, noted in a Sept. 1 interview that the bathtub curve phenomenon is well established among industries working through the struggles of new technology.

“As new technologies are implemented, along with those new technologies come new failure methods. You may not understand all the failure modes as you’re implementing the new technology,” Hall said.

But he agreed that the rapid construction of pipelines in the U.S. is likely a contributing factor to “people … out there possibly taking shortcuts or not being as diligent” as they would be if the pace of construction were less fervent.

The NTSB’s mission — to investigate accidents — is inherently backward-looking, but Hall said he and his team try to stay abreast of issues they believe may become critical factors in accidents in the near future.

Linda Daugherty, a deputy associate administrator for field operations at PHMSA, during a recent public meeting agreed that the bathtub curve phenomenon is a useful one to help target inspections and to educate regulators on areas that need closer attention. However, she cautioned against applying the trend too broadly and presuming that all pipelines installed during recent years pose higher risks.

“We’ve got to be careful with the metrics we choose, and we’ve got to understand the context,” Daugherty said Aug. 25 at a joint meeting of the gas and liquid pipeline advisory committees.

The Interstate Natural Gas Association of America agreed with Daugherty’s remarks, and spokeswoman Cathy Landry emphasized the importance of learning from the data and getting a better handle on what it means.

“We believe it’s important to really look at the information and what it means. Certainly, we can learn lessons from this information, and we must evaluate it to understand if something is going on. There are lessons to be learned,” Landry said Sept. 9. “Still, as Ms. Daugherty points out, it’s not a good idea to just jump to the conclusion that there’s something systemically wrong with a whole host of pipelines.”