Fracking Contamination Case Can Go to Trial

January 4, 2017Methane Plumes Downwind of Natural Gas Compressor Stations

January 26, 2017by Melissa A. Troutman, Sierra Shamer and Joshua B. Pribanic, Public Herald

After a three-year investigation in Pennsylvania, Public Herald has uncovered evidence of widespread and systemic impacts related to “fracking,” a controversial oil and gas technology.

Ending over a decade of suppression by the state, this evidence is now available to the public for the first time.

In Pennsylvania, the power over fracking rests in the hands of the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). When residents observe a problem, they call the Department to report it. That call gets recorded as a “complaint” as required by Chapter 58 § 3218 of the state’s oil and gas act.

After pushing through DEP’s resistance to disclose these records, our team was able to conduct its first file review for complaints in the spring of 2013. Three years later, after more than 50 file reviews, Public Herald has scanned records for 6,819 complaint cases.

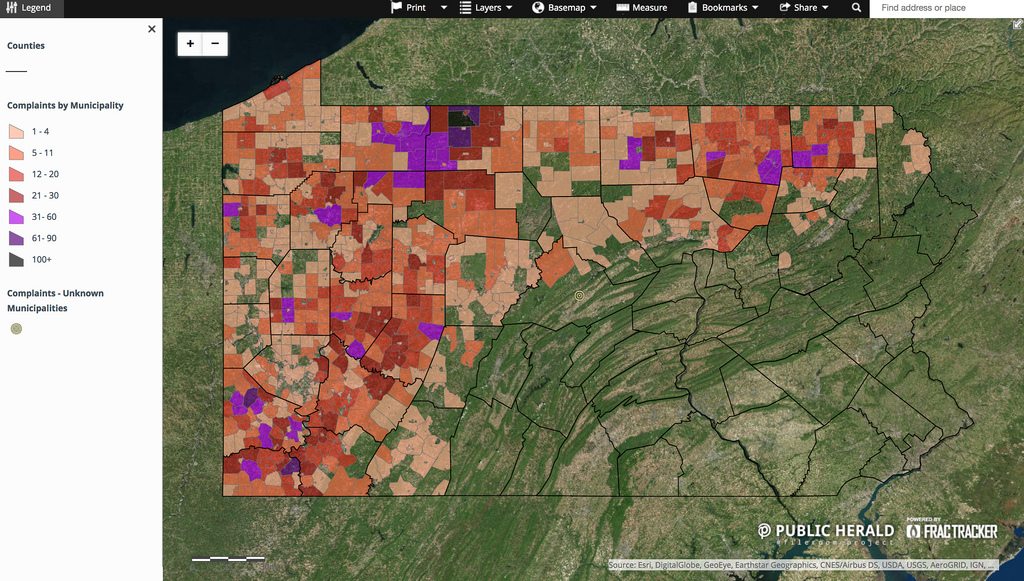

Today, due to this work, anyone can access these cases via the Pennsylvania Oil & Gas Complaint Map.

This map shows how citizen complaints are dispersed across counties where shale gas drilling has occurred. We shared our dataset with several scientists, including Dr. Anthony Ingraffea, an oil and gas engineering expert from Cornell University whose work on fracking is published in multiple peer-reviewed papers.

“It’s not like all the bad stuff is happening up in the northeast. Pennsylvania is pretty widespread, and what the data shows, quite clearly, is that impact has been systemic.”

At the end of our reviews, we submitted a final Right-to-Know request for the DEP database of all citizen complaints. On December 30, 2016, DEP responded in an email with a new list revealing a statewide total of 9,442 complaints from 2004 through November 29, 2016.

The total number of complaints in the databases ended up being thousands more than anyone on our team had anticipated.

When we compared the annual number of complaints in Pennsylvania to unconventional shale gas development – a.k.a. “fracking” — it revealed a strong relationship.

If you include conventional wells as a variable, the rise of impacts clearly increases with the rise of fracking development.

In the graph above, Dr. Ingraffea identified the years 2004 and 2005 as “baseline” or “what things were like in Pennsylvania before shale gas fracking really got started.”

During that time, Ingraffea calculated that there was one complaint for every ten conventional wells drilled – then things clearly changed.

“When transitioning to unconventional wells [there] is typically one complaint per well. Even though the industry has had over a decade to learn its lessons and figure out how to get things right, in the last few years the number [has increased to] two complaints for every well drilled.”

This increase in complaints per unconventional well is unexpected, given the recent decrease in drilling activity throughout the state. For Ingraffea, the data illustrates that the situation is getting worse by the year.

“If you drill a shale gas well in Pennsylvania today…the data says you are more likely to get a complaint now than in 2010.”

In fact, when Governor Tom Wolf took office in 2015, after campaigning on the promise to make fracking “safe,” the number of complaints exceeded the number of new shale gas wells for the first time since 2009.

Dr. John Stolz of Duquesne University in Pittsburgh is another scientist at the forefront of this issue who has conducted independent water investigations of areas impacted by fracking since 2010.

After reviewing this new data, Dr. Stolz. said, “Just looking at the raw numbers, you can say that unconventional wells, for whatever reason, generate more complaints per well. That’s something the DEP should be concerned about.”

Of the complaint total, 4,108 cases are categorized by DEP as “water supply” complaints. However, this is much lower than the actual number involving drinking water supplies. Hundreds of additional cases are categorized by DEP as gas migration, spill response, pollution, or leaking wells which can include impacts to water.

Throughout Pennsylvania, DEP has determined that only 284 water supplies have ever been impacted by oil and gas operations in the state. This means that DEP considers 94% of drinking water complaints to be completely unrelated to oil and gas.

“You’re telling me that there are thousands of people [who say their water was impacted by oil and gas] in Pennsylvania that want to fool the DEP? I can’t accept that,” said Dr. Stolz.

According to Ingraffea, “This goes to the very heart of the meaning of this data – are the complaints pie in the sky, crying wolf…or are they real?”

“The question on a lot of people’s minds, including myself, is – ‘Does unconventional extraction pose a threat to drinking water?’ If you suppress [complaint] information, it’s very difficult to make a case.” – Dr. John Stolz

The United States Environmental Protection Agency concluded a five-year study in 2015 that stated fracking had no “widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water supplies.”

But less than a year later, the EPA’s own Science Advisory Board (SAB) called them out. In an August 2016 review, the SAB stated that EPA did not have the evidence to make such a conclusion.

This forced the EPA to retract their “widespread” and “systemic” claims in December 2016. In their final report, the agency states that fracking can cause water contamination, but they fail to make a broader conclusion citing insufficient data.

EPA used several sources of data from DEP, including the Department’s oil and gas compliance database of inspections and violations. In a call with Public Herald, EPA’s Jeff Frithsen could neither confirm nor deny whether the Agency reviewed any DEP complaint data for its study.

This isn’t the first time EPA has studied the relationship between fracking and drinking water pollution. In fact, the Agency has linked fracking to drinking water contamination as far back as 1987 when “fracking fluids migrated” into a West Virginia water supply.

When a person’s water becomes contaminated, the issue isn’t whether impacts from fracking are “widespread” or “systemic.” The issue is far more tangible – you’ve lost your water.

Filing a complaint is not rewarding or easy. Calling Pennsylvania DEP begins a process that most often leaves a resident with ongoing pollution problems and feelings of hopelessness.

Janet McIntyre is a resident of the Woodlands, a neighborhood in Connoquenessing Township, Butler County. After shale gas wells were constructed nearby, residents in the Woodlands began experiencing water problems. DEP investigated these complaints, but determined that they were not related to oil and gas activity.

Janet and her husband, along with 50 of their neighbors, have relied on donated, bottled water ever since – six years and counting.

According to Janet, when she asked how to appeal DEP’s “non-impact” determination, Deputy Secretary of Oil and Gas Scott Perry told her that it was impossible because the agency acts as “both judge and jury.”

But later, Janet learned that the Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board considers no action of the DEP final until an adversely impacted person has had the opportunity to appeal the action.

Perry has also publicly dismissed legitimate concerns about fracking’s effects on drinking water by insinuating that people are looking for something that’s not real.

“I feel like I’m trying to convince the public that Sasquatch doesn’t exist,” said Perry at an industry convention in 2011.

Desperate for information, Janet asked DEP for her complaint file. DEP failed to provide it to her, fortunately for Janet it was among the 271 complaints Public Herald had scanned for Butler County.

Dr. Stolz has conducted a case study of the Woodlands since 2010, and in all his research, he never found residents’ complaints in any of the files that DEP provided to him.

“A big part of the problem is that [officials] don’t take these complaints seriously,” Stolz said. “But when you go out and you meet people…you realize that this is for real. And until that attitude changes in Harrisburg, we’re going to continue seeing these complaints swept under the table.”

In their 2015 annual report, DEP described a plan to create a “Water Supply Complaint Tracking System.”

In late 2016, DEP added an interactive report of resolved drinking water complaints to their website. DEP did not respond to questions about exactly when this report was added, though it coincided with Public Herald’s final Right-to-Know request for all citizen complaints at the end of our investigation.

While this is a step toward transparency, it is only a list – no records are available to view or download.

Without access to the full complaint record, the public cannot see how DEP inspectors investigate. It’s also impossible to see the details of each complainant’s call, their water test results, or the determination letters issued.

The records provide invaluable insight into a caller’s experience and an inspector’s conduct during the investigation.

You can also see people’s descriptions of their water problems, like foaming or bubbling, bad odors, and strange colors. In other cases, residents experience stomach aches, rashes, hair loss, dead animals, and even hospitalizations.

While DEP’s annual report “highlights ongoing data trends” for violations, compliance, stray gas migrations, and other issues, the agency fails to include any trend analysis of oil and gas complaints.

Why is this important?

After twelve years of oil and gas development, the secrecy surrounding complaints has prevented scientists, policymakers, and medical professionals from doing their jobs and has kept the impacts of fracking underground.

“This level of complaints is not good business practice,” remarked Dr. Stolz. “We’re talking about at least 100,000 wells when all is said and done. At that level, all DEP will be doing is fielding calls for complaints. That’s a real concern, and it needs to be addressed.”

Over the past four years, DEP has received an average of three oil and gas complaints per business day, with just over 10,000 unconventional wells drilled. At this rate, with 100,000 wells, DEP could be responding to an average 30 complaints related to fracking every day.

The projected rise in complaints would likely place a huge financial burden on DEP’s shoulders, a burden carried under the weight of a decreasing budget and a legal mandate to permit new wells.

Since 2004, the agency has permitted 21,980 unconventional wells – to date, only half have been drilled.

It would be reasonable to think that the Department would conduct its own complaint analysis and report those findings to the state legislature, which has the power to either limit the expansion of fracking, increase the breadth of DEP’s resources, or both.

But that’s not what DEP is doing.

DEP has concluded that out of thousands of drinking water complaints that residents attribute to oil and gas activities, only 6% of these are related.

This means that thousands of people in shale gas counties, living near fracking operations, are experiencing water problems that DEP claims have nothing to do with oil and gas.

So why, then, are so many people noticing changes to their water? And what is really causing those changes? What evidence does DEP have that proves oil and gas is not responsible?

Public Herald dove into the complaint records to find this out.

In 2015, we reviewed 200 cases and discovered ways that DEP ignores, excuses, and dismisses evidence that indicates impact from oil and gas activities.

After our initial analysis, we tried to meet with Governor Wolf and former DEP Secretary John Quigley to discuss the Department’s actions, but our requests were declined.

As our complaint database grew, we began an in depth analysis in search of further evidence.

For this report, Public Herald has reviewed over 1,000 drinking water complaint cases in Pennsylvania. Our analysis reveals shocking evidence of misconduct within DEP that includes and exceeds mere negligence.