Our Dirt Roads: Dump Sites For Oil & Gas Well Wastewater?

March 24, 2019

International Human Rights Court Recommends Worldwide Frac Ban

April 5, 2019By Nick Cunningham, Yale Environment 360, March 21, 2019

Pittsburgh is a city on the upswing, rebounding this century from its rustbelt past by developing more innovative sectors such as health care, education, and technology. Uber is testing its self-driving cars in Pittsburgh. Carnegie Mellon University is home to a world-renowned Robotics Institute. And the city made an aggressive bid for Amazon’s HQ2, which the mayor viewed as key to moving the Steel City beyond its roots in heavy industry.

Progress toward a cleaner, post-industrial future is not linear, however. Although the air in Pittsburgh has dramatically improved from the days when it was one of America’s most polluted cities, it still contains high levels of hazardous pollutants, in large part because of several major steel foundries and coke works still in operation, according to the Clean Air Council. The rise of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas, now more than a decade old, has exacerbated regional air quality problems. Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, is out of compliance with federal air quality standards on fine particulate matter (PM 2.5) and sulfur dioxide. In 2018, the region barely met the federal ozone standard after falling short in years past.

Now, Pittsburgh and the surrounding area are embracing a new wave of industry tied to the fracking boom in western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Nothing better embodies this surge than a massive, $6 billion ethane cracker currently being built 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh by Shell Chemical Appalachia, a subsidiary of the oil giant Royal Dutch Shell. The facility will process huge quantities of natural gas and natural gas liquids from the prolific Marcellus and Utica shales and turn them into the building blocks of plastic. The plastic pellets produced by “cracking” ethane molecules will then be sold to manufacturers producing consumer and industrial products such as plastic bags, packaging, automotive parts, and furniture.

When it comes online in 2021, Shell’s ethane cracker will also add significantly to air pollution in western Pennsylvania, becoming the region’s largest source of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are harmful gases emitted by solids or liquids, including combusted fossil fuels. The facility will also emit substantial amounts of nitrogen oxide (NOx), sulfur dioxide (SO2), fine particulate matter, and other hazardous air pollutants, the Clean Air Council says. All of these have been linked to an increased risk of respiratory problems such as asthma, as well as to cardiovascular effects and a heightened risk of cancer.

Environmental groups, along with some local residents, have fought the ethane cracker. But local and state political leaders are almost uniformly supportive of the project, regardless of party affiliation. So are labor leaders and many local citizens, seeing the arrival of Shell’s facility as a pivotal moment in the creation of a new, large-scale industrial sector that could rival the region’s glory days of steel production.

“Employment in western Pennsylvania has never been better,” says Ken Broadbent, business manager at Steamfitters Local 449, noting that construction at Shell’s ethane cracker will eventually provide jobs for 1,500 steamfitters, some of whom will make more than $100,000 a year. “I’ve never seen this many jobs for construction workers in western Pennsylvania, and I’ve been a steamfitter for 45 years. Natural gas is going to be bigger than the steel industry back 30 or 40 years ago. There’s 50 years to 100 years of natural gas in this tri-state region. This thing is not going away.”

Asked if he is concerned about air pollution from the plant, Broadbent acknowledged the threat, but said the economic opportunities are too important. “It concerns everybody — we fish, we hunt, our kids breathe the air like everybody else,” he said. “But we’ve also got to realize that people have got to work for a living, too. If you’re not working, it won’t matter how much pollution you have.”

Construction of the Shell facility is expected to reach its peak this year, with up to 6,000 total workers on site. When operational, the plant will employ 600 people on a permanent basis.

Pennsylvania’s Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, has hailed Shell’s ethane cracker as the “biggest private-sector investment in Pennsylvania since World War II” and touted the prospect of a transformation of western Pennsylvania as a fracking-driven energy “hub,” with the cracker just the first in a series of petrochemical projects. Executives and industry analysts refer to Shell’s ethane cracker as an “anchor” project around which new infrastructure would be built — the associated pipelines, compressor stations, gas processing facilities, and a new ethane storage facility.

But this reindustrialization of western Pennsylvania, and the resulting increase in air and water pollution, is of growing concern to some in the region. They note that in recent years the Pittsburgh area has benefitted from a job-creating shift to cleaner economic sectors, driven by major local institutions like the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

“This region for [the last] 30 years started making some really smart decisions — investing in education and health care, letting universities lead the way, letting innovation be the driver, having a much more diversified economy and, especially, climbing up the value chain and getting away from those basic commodities that leave a toxic legacy,” says Matt Mehalik, executive director of the Breathe Project, a local nonprofit working to reduce air pollution.

Others see the arrival of the ethane cracker as further evidence of the fracking industry’s increasing dominance of western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Although the fracking boom has undeniably created jobs and pumped money into the region, scientists and environmentalists say it is bringing with it polluted wastewater, dirty air, roads crowded with gas industry trucks, and rural areas dotted with noisy and unsightly drilling platforms.

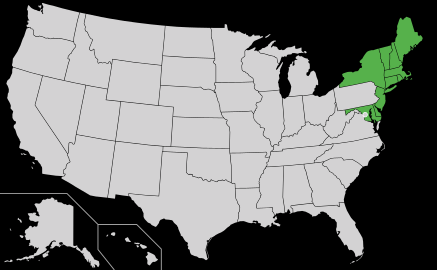

Ted Auch of the FracTracker Alliance, a non-profit that keeps tabs on the health effects of the shale gas industry, notes that it has gone through several phases over the past decade. At the start of each phase, he says, the industry pushed for new investments that justified the next level of intensification. First, the industry needed more pipelines in order to move excess gas out of the region. Then it needed more wells to dispose of fracking wastewater, says Auch. Then the ability to export gas abroad. A year ago, exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) began from a newly constructed terminal on the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, moving Marcellus shale gas across the world to Japan.

Auch says he fears that Shell’s ethane cracker, plus others in the works, may unleash yet another wave of drilling. “So now we’re on like our third or fourth version of reasoning for why [the industry] needs X, Y, and Z,” says Auch.

Auch and others say that at a time when scientists are issuing increasingly stark warnings about the worsening impacts of global warming and the need to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the fracking boom in northern Appalachia, coupled with the construction of related infrastructure and facilities, is moving the region and the U.S. in precisely the wrong direction. They note that in 2017 the city of Pittsburgh unveiled an ambitious plan to slash greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030 (using a 2003 baseline), which would equate to a reduction of 2.1 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. Shell’s ethane cracker, which needs to burn natural gas to create the high temperatures needed to “crack” ethane, is expected to emit 2.2 million tons of greenhouse gases annually. In other words, all of Pittsburgh’s work on combatting climate change through 2030 would be negated by a single plant.

The plant’s critics also maintain that Shell’s ethane cracker represents a significant setback in the region’s long battle to clean up its air. Pittsburgh is ranked in the top 10 nationwide for most polluted cities in terms of year-round particulate matter. Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, is ranked in the top 2 percent nationally in terms of cancer risk from hazardous air pollutants, according to a 2013 study by the Center for Healthy Environments and Communities at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

Shell refutes the notion that its Pittsburgh-area ethane cracker will adversely affect the health of nearby communities. “Shell takes the health of the community and our staff very seriously,” says Joe Minnitte, a company spokesman. He notes that the potential health effects from hazardous air pollutants were evaluated when Shell applied for, and received, its air permits from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (PA DEP). Indeed, the DEP concluded that the air and health impacts would not exceed federal standards.

“Inhalation risk assessments performed by Shell and PA DEP during that period concluded that chronic cancer and non-cancer risks as well as acute non-cancer risks do not exceed PA DEP’s benchmarks,” Minnitte says. Shell agreed to implement air quality monitoring around its facility.

Moreover, Shell purchased pollution credits to offset its emissions. Industrial emitters frequently buy such credits, particularly in areas that don’t meet federal air quality standards. In Shell’s case, however, this has been controversial, because while the company secured enough credits for its nitrogen oxide pollution, it could not find enough credits for its VOC emissions. So it lobbied the Pennsylvania DEP to convert surplus nitrogen oxide credits into VOC credits. While this may help reduce pollution in a neighboring county from a shuttered facility, pollution will increase in the vicinity of the cracker plant when it comes online, opponents warn.

Another ethane cracker about 75 miles downriver in Ohio — backed by PTT Global Chemical, a Thailand-based petrochemical giant, and its Korean partner, Daelim Industrial Co. — has cleared the regulatory process and expects a final investment decision soon. A third ethane cracker has been proposed nearby in West Virginia. A 2017 report from IHS Markit, an industry consulting firm, found that northern Appalachia – the tri-state area of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia – could support four additional crackers after Shell’s project comes online.

According to the Breathe Project, the Shell facility, plus the PTT Global Chemical and the West Virginia plant, could result in additional health care costs of $20 million to $46 million annually just for Beaver County, where Shell’s facility is under construction. Those estimates include treatment for increased respiratory ailments, lung cancer, asthma, and cardiovascular disease, as well as for loss of work. Neighboring Allegheny County, where Pittsburgh is located, could see $14 million to $32 million in additional health care costs annually due to the toll exacted on public health from the three plants, the Breathe Project estimated, based on modeling used by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Those numbers only accounted for fine particulate matter, not the array of other pollutants expected from the plant. In addition, the region already is impacted by the pollution, including methane leaks, from thousands of shale gas wells, compressor stations, and storage facilities.

Shell’s ethane cracker alone would require 1,000 fully producing shale gas wells to feed it on an ongoing basis, according to John Stolz, director of the Center for Environmental Research and Education at Duquesne University. But he notes that shale gas wells are known to have steep declines in their production rates, meaning that many more wells will need to be drilled to keep the cracker plant running for decades to come.

Some citizens in the region already are alarmed by the health and environmental impacts of the fracking boom. Allen Young is a correctional officer who lives roughly a mile or two from a shale gas well in Powhatan Point, Ohio that exploded and leaked gas for several weeks in February 2018 before it was contained by its owner, XTO Energy, a subsidiary of ExxonMobil. In the days following the explosion and gas leak, Young, his wife, and their two children started having nosebleeds, headaches, and respiratory problems, which he attributes to the leak.

When asked about the possibility of several ethane crackers coming into the region, including the proposed PTT Global Chemical cracker that would be built just a few miles from his house, Young replies, “I’ve seen firsthand there’s no regulation with these people. They do what the hell they want, when they want, how they want to do it. Money talks … This is kind of like the little Cancer Alley of the Ohio Valley.”

Young was referring to Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” a stretch of petrochemical and chemical facilities along the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge that has been emitting toxic pollution into nearby communities for decades. Late last year, the U.S. Department of Energy laid out the case for locating a network of petrochemical plants in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, citing the national security concerns of having too many storage and petrochemical facilities concentrated near the Gulf of Mexico coast due to its vulnerability to natural disasters — a danger that will only grow as the climate continues to change.

The ethane crackers under construction or planned in the Ohio River Valley are illustrative of a broader wave of investment flowing into petrochemicals. According to the American Chemistry Council, from 2010 to late last year, more than $200 billion in investment poured into 333 chemical and petrochemical projects in the U.S., much of it “geared toward export markets for chemistry and plastics products.”

Although the growth in consumption of natural gas and oil is expected to slow worldwide in the decades ahead, in part because of the wider adoption of electric vehicles, no end is in sight for the consumption of plastic. “Petrochemicals are rapidly becoming the largest driver of global oil consumption,” the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in a 2018 report. By mid-century, according to the IEA forecast, petrochemicals will account for half of the total growth in oil demand – more than trucks, aviation, or shipping.

It’s increasingly common for consumer plastic to make a mind-boggling journey that begins with drilling for oil and gas in Texas, separating out the various natural gas liquids from one another, cracking the ethane to produce polyethylene along the Gulf of Mexico coast, and shipping the plastic pellets to Asia to be processed into plastic wrap or packaging, which is then shipped back to grocery stores in the U.S. Ultimately, when that plastic reaches the consumer, it is often used once and discarded in a matter of minutes or seconds. The climate impact is profound. Carbon dioxide emissions from the petrochemical sector are expected to rise by 20 percent through 2030, according to the IEA.

In the Ohio Valley, the lure of major sources of new employment in a region that has seen an exodus of industries is hard to pass up, says Mehalik of the Breathe Project. But he adds that these communities shouldn’t have to bear the burdens of pollution that might also preclude other forms of cleaner economic development. Pittsburgh’s recent comeback has had little to do with heavy industry, Mehalik says, and the emergence of a major petrochemical industry puts a lot of that progress in jeopardy.

“So now, all of a sudden, it’s like, ‘Here we go again,’” says Mehalik. “It’s like we’re going back on a bender, doing things that we know are bad for us. And yet it’s happening. That, to me, is the ultimate outrage. It’s just an insane economic development strategy.”