Interview with Environmentalist Wilma Subra

February 3, 2020

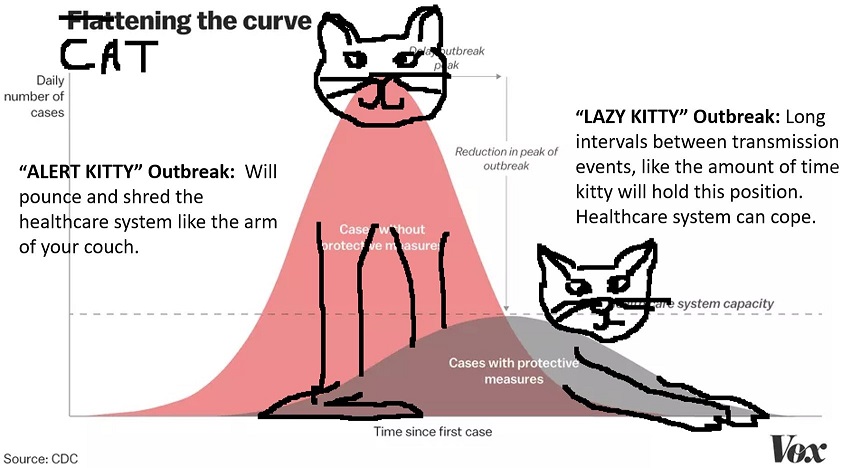

Stay Well: Information on COVID19

March 19, 2020By Justin Nobel, Rolling Stone, January 21, 2020

![]()

Rolling Stone’s Justin Nobel reports about the trillions of gallons of radioactive waste from oil and gas drilling that is being dumped in our waterways, on public roads, and into waste facilities; how this radiation is poisoning workers and finding its way into all of our backyards and homes; and the lack of regulatory control or even acknowledgment of the problem. DCS was an important resource for this deeply researched article, providing contacts and information. We are so glad to see attention paid to a public health situation what will only get worse and cause more harm in the future unless stopped now.

The article is lengthy but clearly written and well worth reading. But for those who may not have the time to read it in detail, here are a few highlights:

- “The most common isotopes are radium-226 and radium-228, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission requires industrial discharges to remain below 60 for each. Four of Peter’s samples [of natural gas drilling brine] registered combined radium levels above 3,500, and one was more than 8,500.”

- “If I had a beaker of that [Marcellus Shale brine] on my desk and accidentally dropped it on the floor, they would shut the place down,” says Yuri Gorby, a microbiologist who spent 15 years studying radioactivity with the Department of Energy. “And if I dumped it down the sink, I could go to jail.”

- “Used for home patios, sidewalks, and driveways — ‘Safe for Environment & Pets,’ the label touts — AquaSalina [waste from oil and gas wells packaged and sold at retail] was found by a state lab to contain radium at levels as high as 2,491 picocuries per liter.”

- “Resnikoff, who assessed the DOT rule in 2015, said the standard brine truck in Pennsylvania would be ‘1,000 times above DOT limits.’ Which would mean they’re breaking the law. ‘There isn’t anything specifically preventing them from doing that,’ says the DOT spokesman. Testing, he said, is the responsibility of the operator at the wellhead who dispatches the brine to the hauler, and so the system mostly relies on self-reporting.”

- “While large bodies of water like lakes and rivers can dilute radium, Penn State researchers have shown that in streams and creeks, radium can build up in sediment to levels that are hundreds of times more radioactive than the limit for topsoil at Superfund sites.”

- “’There is nothing to remediate it [soil contaminated with runoff from brine-treated roads] with,’ says Avner Vengosh, a Duke University geochemist. ‘The high radioactivity in the soil at some of these sites will stay forever.’ Radium-226 has a half-life of 1,600 years.”

- “[T]hanks to a single exemption the industry received via the Bentsen Amendment to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act in 1980, re-labeling the wastes from oil and gas as “special,” followed by the refusal of the EPA to oversee the waste as harmful, the streams of waste generated at oil-and-gas wells — all of which could be radioactive and hazardous to humans — are not required to be handled as hazardous waste. … [though] the agency found concerning levels of lead, arsenic, barium, and uranium, and admitted that it did not assess many of the major potential risks… the report focused on the financial and regulatory burdens, determining that formally labeling the ‘billions of barrels of waste’ as hazardous would ‘cause a severe economic impact on the industry’” therefore establishing the current dangerous situation.

In 2014, a muscular, middle-aged Ohio man named Peter took a job trucking waste for the oil-and-gas industry. The hours were long — he was out the door by 3 a.m. every morning and not home until well after dark — but the steady $16-an-hour pay was appealing, says Peter, who asked to use a pseudonym. “This is a poverty area,” he says of his home in the state’s rural southeast corner. “Throw a little money at us and by God we’ll jump and take it.”

In a squat rig fitted with a 5,000-gallon tank, Peter crisscrosses the expanse of farms and woods near the Ohio/West Virginia/Pennsylvania border, the heart of a region that produces close to one-third of America’s natural gas. He hauls a salty substance called “brine,” a naturally occurring waste product that gushes out of America’s oil-and-gas wells to the tune of nearly 1 trillion gallons a year, enough to flood Manhattan, almost shin-high, every single day. At most wells, far more brine is produced than oil or gas, as much as 10 times more. It collects in tanks, and like an oil-and-gas garbage man, Peter picks it up and hauls it off to treatment plants or injection wells, where it’s disposed of by being shot back into the earth.

One day in 2017, Peter pulled up to an injection well in Cambridge, Ohio. A worker walked around his truck with a hand-held radiation detector, he says, and told him he was carrying one of the “hottest loads” he’d ever seen. It was the first time Peter had heard any mention of the brine being radioactive.

Continue reading here or

Download the article as a pdf.

Download A Dangerous Secret That Could End Fracking, an interview with investigative Journalists Justin Nobel and Joshua Pribanic.

For more information, see our Toxic Frac Brine page.

See a map of unpaved roads in PA that could become legalized dumpsites for millions of barrels of toxic frac waste.