Delaware River Frack Ban Coalition to DRBC: Pass a FULL BAN on Fracking

September 14, 2021

Remembering Ed Wesely

October 12, 2021By Jon Hurdle, NJ Spotlight News, October 4, 2021

It was the community that won it.

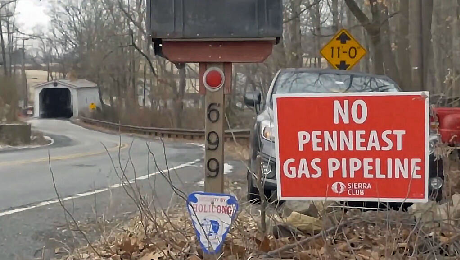

The PennEast Pipeline Co.’s decision to end its plan to build a natural gas pipeline through about 40 miles of New Jersey’s public and private lands was fundamentally the result of sustained grassroots opposition from the communities where the pipeline would have been built, according to advocates, lawmakers and local activists.

The company’s plan to take lands by eminent domain if necessary to build a fossil-fuel pipeline widely viewed as unnecessary enraged residents along the route from the moment it was announced in 2014. That outrage influenced some local and county officials, state and federal lawmakers, and the administration of Gov. Phil Murphy, whose Department of Environmental Protection denied permits, leading the company to unilaterally pull out.

The state argued against PennEast’s plan to use eminent domain to build the pipeline in a case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The project, and its opposition, prompted federal legislation that would stop energy companies from justifying pipeline projects by agreeing to sell the fuel to their investors, and became a rallying cry for local environmental groups and land-rights advocates.

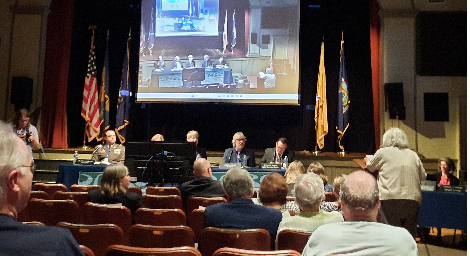

Starting it all was strong opposition at the community level, said state Sen. Christopher “Kip” Bateman, a Republican representing parts of Hunterdon, Mercer, Middlesex and Somerset counties.

“That was probably what determined PennEast’s decision to pull back,” said Bateman, who opposed the project from the start. “There were a number of property owners, they were going to have to condemn their land. The property owners weren’t going to let them on the land. This was really a grassroots effort at the local level by the citizens of those areas, so I think that had a great deal to do with defeating this proposal.”

Failure to get key permits

That pressure spread to lawmakers and to regulators at the DEP who were seen as unlikely to issue the required water-quality permits if PennEast applied again. In its statement last Monday, PennEast cited its failure to get DEP permits in its decision to pull out.

Bateman said he wrote “at least twice” to the DEP, asking it to deny permits, and said many other lawmakers and officials also responded to public pressure.

“You had the local mayors, county commissioners, state legislators and congressmen and women, all opposed to it, sending letters and reaching out to the regulators,” he said. “We were listening to our constituents and doing our job, expressing their dissatisfaction about the project to the regulators, and I think that had a lot to do with it.”

In June, PennEast won an important victory when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the company had the right to take 42 parcels of state land to build the pipeline.

But less than three months after that ruling, PennEast threw in the towel, apparently because it had simply run out of time, Bateman said. “Once time went on and on and they hadn’t done their proper surveys, and they hadn’t been able to acquire the land they needed, it was in favor of the opposition.”

Legal obstacles

That analysis seemed to be confirmed in a new statement by PennEast spokeswoman Pat Kornick, who said on Tuesday that the company quit because of continuing legal obstacles.

“The uncertainty surrounding the additional time it will take to have final resolution to legal challenges and regulatory hurdles is the driver behind PennEast’s decision to cease development of the project,” she said. Kornick declined an interview request.

The company signaled its pullback by saying last month that it would not take the state lands despite the high court’s ruling. It left open the possibility of reviving the project in future but firmly ended its plan last week.

In 2018, PennEast sued 130 New Jersey landowners who refused its offers of compensation for plans to build the pipeline on their properties. The company wanted to use eminent domain to take a total of 154 acres, most of which was in Hunterdon County.

Maya van Rossum, leader of the environmental group Delaware Riverkeeper Network, said community pressure was the starting point for a series of legal actions and advocacy campaigns since the project was announced.

Public protests, pressure

She argued that public protest and advocacy led the Delaware River Basin Commission to direct PennEast to apply for a permit that covered the entire pipeline route. The pressure, she said, later resulted in the regulator telling the company it needed to seek permission before cutting down trees.

Public pressure also prompted some New Jersey lawmakers to speak out against the project, and underpinned legal challenges that slowed down the approval process at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, said van Rossum, whose group was a leading advocate against PennEast.

“There is not a single step where the public did not inspire opposition, increased reviews, or slowed process,” she said.

Supporters of the opposition movement included U.S. Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-12th), who spoke at a video conference last Monday to celebrate the PennEast decision.

“This is such an important victory,” she said. “It makes me so proud to be a Jersey woman because New Jersey, from the government to the people, to the residents, to the advocates, all stuck together. I’m so delighted that the pipeline realized that you were neither needed nor wanted, and that we would collectively stand up to make sure it didn’t happen.”

T.C. Buchanan, a Hunterdon County landowner who would have been forced to have the pipeline built on her property, said she had been inspired by Watson Coleman’s opposition to the pipeline, and hoped the campaign will be an inspiration for others.

“When I first heard her speak against this pipeline, it gave me hope,” she said during the conference. ”I held back tears for seven years while my property was being raped by surveyors. I was not letting myself cry because I needed to be strong. Now, it’s gratitude, it’s relief, it’s letting loose all those other tears that have been held back. We can prove to humanity that people who don’t even know each other can come together and make change for the better.”

Jacqueline Evans, another Hunterdon County landowner, and a founder of the campaign group HALT, or Homeowners Against Land Taking, said it proved that community action can succeed in the face of corporate power.

“By forming the group, we gave voice to so many property owners and showed that we could do so much more together than alone,” she said. “So many people told us that we didn’t have a chance. We never believed that, and we always kept fighting. Through this, we have protected our children, their future, our communities, agriculture, the local economy. There was so much worth fighting for. This was a huge win, and I’m glad it’s finally over, and I hope other pipeline fights can benefit from the work we’ve done here.”