Radioactivity Levels Found Outside Ohio Oilfield Waste Facility Called ‘Excessive’

April 30, 2022

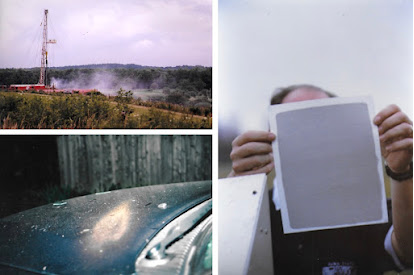

Drillers Dispose of Drill Cuttings by “Dusting” – Blowing Them on the Ground, and in the Air

May 6, 2022By Mark Michaud, University of Rochester Medical Center, April 11, 2022

New research documents for the first time the pollution of public water supplies caused by shale gas development, commonly known as fracking, and its negative impact of infant health. These findings call for closer environmental regulation of the industry, as levels of chemicals found in drinking water often fall below regulatory thresholds.

“In this study, we provide evidence that public drinking water quality has been compromised by shale gas development,” said Elaine Hill, Ph.D., an associate professor with the University of Rochester Departments of Public Health Sciences, Economics and Obstetrics & Gynecology. “Our findings indicate that drilling near an infant’s public water source yields poorer birth outcomes and more fracking-related contaminants in public drinking water.”

The new paper, which appears in the Journal of Health Economics, is co-authored by Hill and Lala Ma, Ph.D., with the University of Kentucky. Hill’s previous research was the first to link shale gas development to drinking water quality and has examined the association between shale gas development and reproductive health, and the subsequent impact on later educational attainment, higher risk of childhood asthma exacerbation, higher risk of heart attacks, and opioid deaths. Her research brings an important perspective to the policy discussion about fracking which has often emphasized the immediate job creation and economic benefits, without fully understanding the long-term environmental and health consequences for communities in which drilling occurs.

This new study is a complex examination of the geographic expansion of shale gas drilling in Pennsylvania from 2006 to 2015, during which more than 19,000 wells were established in the state. Hill and Ma mapped the location of each new well in relation to groundwater sources that supply public drinking water, and linked this information maternal residences served by those water systems on birth records, and U.S. Geological Service groundwater contamination measures. This data set allowed the two to pinpoint infant health outcomes – specifically preterm birth and low birth weight – before, during, and after drilling activity. Preterm birth and low birth weight are associated with a range of negative outcomes, including higher risk for developing behavioral and social-emotional problems, and learning difficulties.

Other studies have shown elevated levels of chemicals associated with fracking in surface water, however, these levels often tend to be below federal guidelines, are not monitored closely, and even if detected do not rise to levels that trigger remediation. The new study indicates that fracking-related chemicals – including dangerous volatile organic compounds – are making their way into groundwater that feeds municipal water systems, and that the potential for contamination is greatest during the pre-production period when a new well is established. With only 29 out of more than 1,100 shale gas contaminants regulated in drinking water, the results suggest that the true contamination level is higher. The study specifically finds that every new well drilled within one kilometer of a public drinking water source was associated with an 11-13 percent increase in the incidence of preterm births and low birth weight in infants exposed during gestation.

“These findings indicate large social costs of water pollution generated by an emerging industry with little environmental regulation,” said Hill. “Our research reveals that fracking increases regulated contaminants found in drinking water, but not enough to trigger regulatory violations. This adds to a growing body of research that supports the re-evaluation of existing drinking water policies and possibly the regulation of the shale gas industry.”

The research was supported with funding from the University of Rochester Medical Center Department of Environmental Sciences and the National Institutes of Health (DP5OD021338).