Non-Chemical Deer Repellent

October 4, 2023

Politics and the PA Supreme Court: VOTE Nov. 7!

October 21, 2023What’s Going On With PA’s Green Amendment?

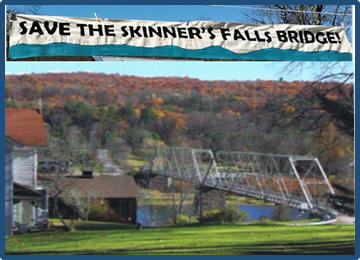

The Delaware River in Autumn. Photo by David Soete.

Download this Blog post as a pdf.

Download the Green Amendments of Pennsylvania, New York and Montana as a pdf.

Pennsylvania has a Green Amendment. It is very similar to Montana’s Green Amendment. So why haven’t we seen a similar climate win for our state based on Pennsylvania’s Green Amendment?

The short answer is, it’s complicated.

Pennsylvania added the Environmental Rights Amendment, Article I, § 27, to its Constitution in 1971. Ratified by Pennsylvania citizens by a margin of nearly 4 to 1, it was incorporated into Article I, Declaration of Rights, and codified the natural rights of Pennsylvania citizens to clean air and water. It thus carries the same weight and status as the rest of our enumerated cherished personal rights like freedom of religion or free speech. Article I, § 27, provides as follows:

The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.

The Green Amendment was well drafted: broad encompassing language that created an enforceable right in present and future citizens to clean air and water. It mandates that Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are publicly owned to be conserved and maintained by the Commonwealth as trustee for the benefit of the citizens.

In 1971, the future of Pennsylvania’s environment looked bright.

From the vantage point of 2023, however, the Environmental Rights Amendment has been a disappointment. From its adoption in 1971 to 2013, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court shackled the provision by adopting a narrow balancing test that weighed the environmental harms caused by the challenged actions against their claimed benefits, and permitted the harms unless they “so clearly” outweighed the claimed benefits. With this test the Supreme Court failed to hold the Commonwealth responsible as trustee of the public natural resources, and failed accord the full weight and significance of the constitutional rights contained in the Environmental Rights Amendment.

The problem lay not with the Amendment but with how the Pennsylvania Supreme Court interpreted it.

The 2013 Landmark Robinson Township Decision

The Court seemed to awaken to the import of the Environmental Rights Amendment in 2013. In the seminal case of Robinson Township v. Commonwealth, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court declared unconstitutional provisions of Act 13, which would have, among other things, permitted the natural gas industry to override local zoning laws if they interfered with the gas industry’s fracking plans. In the decision, Justice Castille took the opportunity to conduct a full analysis of the constitutional amendment and create a framework for its interpretation and application. He was influenced by the resounding approval by the people and their representatives of the Amendment in 1971, indicating their deep desire to create an enforceable right to protect and conserve the air and water quality and public natural resources by placing them in a constitutional trust. Justice Castille rejected the old balancing test as unconstitutional, because it improperly elevated legislative and private industry goals above the people’s constitutional environmental rights. Reversing the Commonwealth Court, he admonished that it was the legislature’s obligation to enact laws that are constitutional, and that a constitutional provision is not subject to override by a legislative enactment. Robinson Township wanted to give teeth to the Environmental Right Amendment.

But that case did not open the floodgates to pro-environmental decisions, because only three out of the total seven judges supported the full opinion, leaving a plurality rather than a majority. A plurality decision is not mandatory precedent so subsequent courts do not have to follow it. In opinions that followed, the conservative Commonwealth Court, which hears appeals from decisions of Commonwealth agencies, did not follow Robinson, choosing instead to revert to the old (unconstitutional) balancing test. Perhaps it was a question of mindset: there were and still are more Republicans than Democrats on the Commonwealth Court. In contrast, the progressive Robinson Township decision, though written by a Republican, was only supported by two other jurists, both Democrats.

The Pennsylvania Children’s Climate Lawsuit

It was shortly after Robinson Township that a group of Pennsylvania children brought a climate change lawsuit in Pennsylvania state court against then-Governor Wolf and others. They argued that the state was constitutionally mandated under the Environmental Rights Amendment to assess the impact of greenhouse gases on the environment and to compel the development and implementation of a plan to control greenhouse gas emission in Pennsylvania. They asked the court to declare that the state had not upheld its duties to protect the environment. The Commonwealth Court disagreed. Dismissal of their case, Funk v. Wolf, in 2016 was affirmed without discussion by the Supreme Court in 2017.

In comparing the Pennsylvania children’s failed climate case to the Montana children’s incredible successful climate change case (Held v. Montana) six years later, we can see one big difference in the focus of the lawsuit. The Montana case challenged the constitutionality of a specific law that prohibited consideration of the environmental impact of any energy project being approved by the state’s environmental agency. The Pennsylvania case swept more broadly, essentially asking the court to order the state to develop and implement a plan to control greenhouse gas emissions. A court is almost always more likely to act on a specific statutory provision than to enforce a general right prospectively.

Looking ahead, the Montana children’s decision, Held v. Montana, will be helpful precedent for future climate cases in Pennsylvania. The Supreme Court has recognized the similarity between Pennsylvania and Montana’s Green Amendments, and in Robinson Township relied on Montana caselaw (pre- Held v. Montana) addressing their Green Amendment in establishing Pennsylvania’s environmental jurisprudence.

Don’t Despair, The Green Amendment Is Gaining Traction

Notwithstanding the disappointing climate ruling in Funk v. Wolf, the Environmental Rights Amendment’s continues to gain traction. Take, for example, Pennsylvania Environmental Defense Foundation v. Commonwealth (2017) (Donahue, J.), which concerned how proceeds from oil and gas leases on public land could be used. There, Supreme Court Justice Donohue reaffirmed and extended Robinson Township and directed that constitutional challenges under the Green Amendment should follow the jurisprudential framework “thoughtfully” laid out in Robinson Township. He emphasized that the State’s Article III police powers are constrained by the people’s “inherent and indefeasible” fundamental rights (such as their environmental rights) in Article I. He reiterated that the State was the trustee, not the owner, of the people’s natural resources, and as such couldn’t use the fracking lease proceeds as it saw fit. Rather, as trustee, it had to use those funds for the benefit of the people and of future generations, in a manner consistent with the terms of the Environmental Rights Amendment.

Just recently, Justice Donahue, in Marcellus Shale Coalition v. Pa. Department of Environmental Protection (2023), rejected a narrow definition of “public natural resources,” noting that this term was always intended to be flexibly defined “to capture the full array of resources implicating the public interest.” Justice Donohue, who has now had several opportunities to study the Environmental Rights Amendment, explained that this amendment “implicates a holistic analytical approach to ensure both the protection from harm or damage and to ensure the maintenance and perpetuation of an environment of quality for the benefit of future generations.”

A recent case also makes challenges under the Environmental Rights Amendment more practical to pursue. Funding environmental rights lawsuits is challenging because they are expensive. They involve costly expert witnesses and time-consuming legal wrangling. This year, in Clean Air Council v. Commonwealth, the Supreme Court made it a little easier for environmental advocates to do their job. The case concerned permits issued by the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) under the Clean Stream Law; specifically, whether a third party objecting to a DEP permit can be reimbursed for their legal fees and costs. Making the DEP or the private party who received the permit pay for an objector’s legal fees is written into the Clean Streams Law, but the Environmental Hearing Board’s practice was to award fees only if the objector could show bad faith in the permitting process. Supreme Court Justice Wecht dispensed with that bad faith requirement. His analysis properly started with a reference to the Environmental Rights Amendment, whose “mandate informs Pennsylvania’s elaborate body of environmental protection statutes and regulations.” According to Justice Wecht, because the Clean Streams Law expressly relies on private citizens to assist in permitting oversight, denying fees and costs to them except under a bad faith scenario has an unwarranted chilling effect.

Our Focus Should Be On The Pennsylvania Supreme Court

Pennsylvania’s Green Amendment’s effectiveness rises and falls with the rulings of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. That court is the final arbiter of the Green Amendment and responsible for providing substance to the amendment’s provisions. But the judiciary can only act in response to lawsuits. Pennsylvanians need to keep using lawsuits to push the environmental rights envelope. Many thanks to those advocates like the Damascus Citizens for Sustainability and the Delaware Riverkeeper who are already doing this on our behalf.

We also have to vote. The Court’s members are elected, but it doesn’t happen regularly. Whenever those elections happen, we have to get out the vote to keep the seats filled with friends of the environment.